Korede has her fair share of concerns in life: a declining familial fortune and social position, a frustrating job as a nurse in a large hospital with an irresponsible staff, a lack of romantic prospects, and a gorgeous but immature younger sister who has an unsavory habit of murdering her boyfriends. However, these problems don’t overlap until the afternoon Ayoola comes to visit Korede’s workplace and picks up the handsome young doctor Korede herself has feelings for—bare weeks after her most recent violent indiscretion and subsequent body disposal.

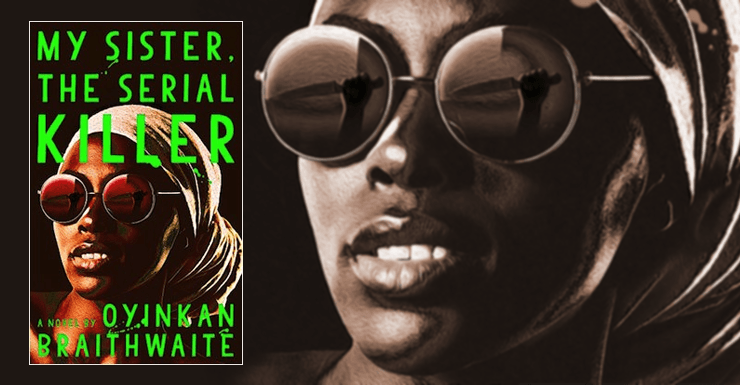

My Sister, The Serial Killer is a high-tension, hideously comedic work of literary horror fiction, a memorable debut from Nigerian writer Oyinkan Braithwaite. Korede’s role as a terse and smart narrator who also happens to lack self-awareness creates a fascinating dual experience for the reader, one that allows Braithwaite to deliver scathing social commentary in scenes her protagonist coasts past without comment or is herself at fault in. The mundane realism of the text—social media, crooked traffic cops, the dichotomy of being wealthy enough for a house maid but not enough to avoid working—makes the ethical questions of murder, consequences, and justification for protecting a family member that much sharper.

Some spoilers follow.

My Sister, The Serial Killer is an abrupt punch of a novel that leaves a commensurate confused ache, sweet-sore around the edges, with its refusal to offer ethically pleasant or neat conclusions. No one is without their sympathetic moments; at the same time no one is without cruelties, be they petty or immense. The sole person who comes off as potentially without blame is the murdered Femi, Ayoola’s third victim and the first one that prompts Korede to question her sister’s veracity. Except it’s still entirely possible that under the poetic public persona Korede saw, he was violent with Ayoola.

From one angle, the novel’s provocative question is: When is it acceptable to murder a man? From another, it’s: When is it acceptable to do damage control if the man is already dead? As My Sister, The Serial Killer progresses, we learn that the sisters killed their wealthy abusive father and weren’t caught. We also learn that it’s within the realm of possibility that Ayoola’s first murdered boyfriend was self-defense, and perhaps the second; Femi, the third victim, is the one that Korede doesn’t believe assaulted Ayoola. However, we cannot be sure of this, either. Furthermore, if Ayoola is seeking out men who will snap and offer her the excuse to murder, finding fault becomes a fascinating, ugly exercise.

Buy the Book

My Sister, the Serial Killer

Ayoola is certainly a serial killer, but Braithwaite does an astounding job of making her appealing without being too appealing or romanticized. After all, she’s still spoiled, cruel, and selfish—vapid when she isn’t being brilliant, not concerned with the trouble she causes her sister, sure of other people’s worship of the ground she walks on. She’d already be in jail if it weren’t for Korede—or so Korede believes, so we the reader would have a hard time disproving it, as we’re only given her unreliable and self-interested version of events. Ayoola is impulsive, violent, and willing to toss Korede under the bus when she has to, but she’s also a victim herself and some of her choices are very understandable.

In contrast, Korede is practical and ruthless. She considers whether or not Ayoola might be a sociopath without once turning the same question inward, despite her willingness to dispose of corpses and lie to the police and Femi’s grieving relatives. Her sole concern is avoiding being caught. Even her attempts to keep Ayoola from posting inappropriate things on social media that would draw attention are oriented around her desire to have total control of her environment, in the same realm of behavior as her dismal treatment of her coworkers whom she all views as misbehaving idiots. Class, obviously, plays an unremarked upon but huge role in Korede’s approach to the world and other people.

I read the second half of the book in a state of aggravated distress, spooling out all the potential variables and endings with increasing dread. It becomes clear that Korede is not as sympathetic or blameless as she seems from her own perspective at the opening, clearer still that Ayoola is without the slightest ounce of remorse or compassion, and clearest yet that Tade is so smitten with surface beauty that it blinds him to his own danger. Braithwaite’s skill at manipulating her audience via sparse but scalpel-precise prose is such that, even in this moment, I still sneer at Tade’s treatment of Korede as she presents it.

Even knowing that what happens to him is unacceptable, even knowing that Korede is as much a villain as her sister, even knowing that his worst crime is being shallow, the reader is so immersed in Korede’s blunt, seemingly-objective narration that Tade’s punishment almost feels just. He has been judged against the other men in a patriarchal society that have abused, used, and lied to these sisters, and in the end he has been found wanting. The effect is both sympathetic and horrifying, forcing the reader into the same complicity as Korede but allowing enough breathing room that the closing scene—Korede coming downstairs to greet Ayoola’s new beau—raises the hairs on the back of the neck.

The realism is the kicker. While My Sister, The Serial Killer has its fair share of bleak comedic timing, it is above all a realistic stab at horror fiction—both commentary and performance. These people are all eminently human and that humanity is the source of discomfort, anxiety, upset: all the emotions we turn to horror to provoke in us. Ayoola murders men who, at bare minimum, objectify her and approach her with shallowness, blinded by her beauty; can she be blamed, after her father’s abuse and her experiences with men afterwards? Korede attempts to exert control over her environment as much as possible, down to her skill with cleaning, and doesn’t have much connection to an ethical framework—so it’s difficult to blame her when she thinks it’ll be easier, the first time, to just help Ayoola dispose of the body instead of going through a corrupt judicial system. The comatose man Korede pours out her secrets to keeps those secrets when he wakes; however, he isn’t the person she’d pretended he might be, and she burns his number rather than keeping in contact with him.

No one is simple, no one is right, and no one is without fault at the close of the novel. Braithwaite’s cutting observations of the social order from the police to the hospital to the aunt who pushes them to waste money they don’t have on a lavish event to commemorate her dead brother—these human moments make it impossible to ignore the horror of murder, of dishonesty, of innocent (or innocent enough) bystanders getting caught in the crossfire. And they get away with it. So, perhaps the horror, much like the incisive social observation, is in the reader’s mind, in the reader’s responses to the text. Braithwaite forces you to do the legwork of her fine, artisanal prose, feel the distress she’s created via tangling sympathy and disgust and morality into a mangled ball. It’s a hell of a debut, that’s for certain.

My Sister, The Serial Killer is available from Doubleday on November 20th.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. They have two books out, Beyond Binary: Genderqueer and Sexually Fluid Speculative Fiction and We Wuz Pushed: On Joanna Russ and Radical Truth-telling, and in the past have edited for publications like Strange Horizons Magazine. Other work has been featured in magazines such as Stone Telling, Clarkesworld, Apex, and Ideomancer.